Raft Implementation with Go: Concurrency and Design Decisions

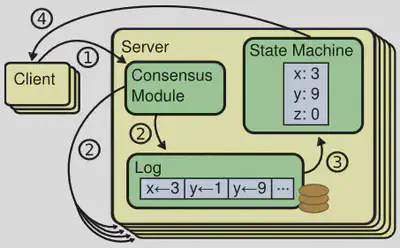

Source: Original Raft paper

Source: Original Raft paperWhy Go?

After learning Go some time ago for building simple, lightweight, fast mid-level systems, I decided to level up my usage of Go for more complex architectures, especially distributed ones. We hear a lot about why Go is a perfect candidate for implementing distributed systems (not to mention a lot of famous distributed systems in CNCF landscape, including Kubernetes, are developed in Go), but I couldn’t find a simple and clean argument explaining why.

Obviously, after starting this blog post like that, I have to present my argument, and that’s exactly what I am going to do! Let’s take a step back for a moment and think about why we need distributed systems in the first place. You might say it’s because monolithic systems cannot scale well, or maintaining such systems is much more flexible since each component (a segment of the entire system) can be maintained by a separate team of developers who publish a complete set of API to other components, thereby enabling different teams for more forward at different development speeds and enhancing isolation. Even recently, with the emergence of edge computing, the distributed design of systems seems a necessary step. All of these reasons are correct but are not the original reasons why software developers started adopting distributed designs. The main incentive behind such design was making software fault tolerant against many forms of failures that lurk around, including network partitions, disk failure, and bugs at various levels. Having said that, distributed systems also come with many disadvantages, most importantly high complexity and costs. Here my main focus is on high complexity.

The complexity in distributed systems is significantly higher compared to monolithic ones because, once our software transitions from a single component to more than one, we have to think about networking aspects as well. A single request and response operation over the network is significantly slower than CPU instruction execution (I recommend taking a look at magic latency numbers to get an idea). Even worse, a single communication might not even compete at all because, for example, an intermediate networking device has dropped packets or due to a network partition. A subtle aspect of networking that should not be overlooked is that a designer must contemplate two sides of networking: the connection between the system’s clients and the system itself, and the connection between the system’s components.

All of these challenges mean that your code should contend with many operations simultaneously. Some of these operations are:

- Check if the internal state is up-to-date

- Wait for the response of a request to a client to come back

- Communicate with peer components to complete a procedure

- Do some computations in the background

As you can see, each component has to do a lot of things concurrently because otherwise, it would be extremely inefficient (most often impossible) to perform the required tasks sequentially.

Thus far, I tried to paint a picture of how and why distributed systems are so complex and what is our initial approach toward these challenges. Now let’s get back to Go. Go programming language is extremely simple (to a degree that most people often call it boring). It has great support for threading (Go call it goroutine). It has a Garbage Collection mechanism that I am so in favor of in the context of distributed systems because it relieves the programmer from thinking about memory allocation/deallocation (don’t forget the fact that when working on a distributed system, the developer is thinking about a lot of aspects that don’t exist when building a monolithic software). Moreover, it is a lightweight, statically typed, and compiled language, which means software written in Go is fast (we want a component to get ready as fast as possible after a crash, for instance), easy to ship (Docker images must be lightweight for faster deployment and migration), and less error-prone (static types can enable the compiler to assist the programmer). Finally, it has a fine set of synchronization utilities.

Now that I have convinced you to use Go for distributed systems, let’s go and discuss some interesting concurrency and design aspects of implementing Raft consensus algorithm, which is the cornerstone of projects like etcd, CockroachDB, and many others.

Setup and dependencies

Before going into the code and design, I have to describe a common ground for implementation.

According to Figure 1, when we are talking about Raft itself, we are only concerned with the consensus module and the log. We interact with clients and state machines through an interface, but we are not explicitly implementing them. Moreover, we need some predetermined scenarios to run and test our Raft implementation.

After conducting research, I found MIT 6.5840’s Labs (2023 version) quite great.

They have provided all of the following:

- A comprehensive infrastructure for developing Raft without having to worry about client and state machines.

- A complete set of test cases to evaluate your implementation.

- Two printing and debugging tools.

I have made some modifications to the provided tools and implemented Raft itself (fully tested). This implementation achieves greater performance (in terms of test case runtime) compared to the reference runtimes provided at the Lab’s page. My implementation with all test results and updated tools can be found in this repository.

Our golden toolkit

In Go’s concurrency world, channels and goroutines are not only first-class citizens but also superstars. Here, I just want to some pretty ways of using these two together:

- Implementing barriers using channels: Have your goroutines send/receive something from a controller/parent goroutine.

- Event-driven programming (my favorite): Have your child goroutines wait for a message from a channel. Upon receiving a message, act based on its value.

- Graceful termination: This a special case of event-driven programming, but to emphasize its importance, I mention it separately.

- Distribution of tasks between actors in Actor programming model.

To implement all those shining use cases you have to utilize Time standard library and select. A general pattern is as follows:

// General pattern for using select, time, and channel

// t is a channel supporting a Timer, Ticker, etc. from the time library

// controlCh is sent from the parent goroutine to

// send various events to this goroutine

// You might want to check for termination somewhere

// in this pattern depending our your use case

for {

select {

case msg :<- controlCh:

switch msg {

case val1:

// Perform scenario 1

case val2:

// Perform scenario 2

}

case <- t:

// Reset/Initialize something or anything else because

// for example a timeout has occurred

}

}

select can have default branch that can be used for non-blocking implementations.Before going into the details of the Raft itself, I should mention that Go supports traditional concurrency primitives, such as Mutex, Condition variable, and Wait groups (for more info look at sync library). However, according to the official documents and many experts, condition variables are not recommended to be used in Go and you can get around with channels and locks instead.

Implementing Raft

Implementing state transition capability

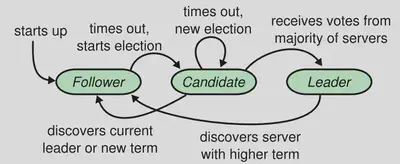

In Raft, we have three states and their relation and transition conditions are as follows:

This might look simple to implement in a client and server, but in a Raft instance, which is a client and server simultaneously, it’s not that easy, and from my experience, a lot of people who are new to concurrency have difficulty implementing something like that.

To figure out what we have to do, let’s break out the places:

- We have several RPC handlers that can respond to

RequestVote,appendEntries, andInstalSnapshotRPCs. - We cannot loop inside a loop to check for state transition events because this would hurt the performance significantly (a lot of sleep and unnecessary operations)

- Trigger for state transition can come from various goroutines

- If state transition happens, we cannot stop all previous operations and start new ones since some functionalities, such as handling RPC requests, overlap in different states.

If you remember our golden toolkit that I introduced above, we can solve this issue with event-driven programming:

func (rf *Raft) main() {

debug.Debug(debug.DInfo, rf.me, "Starting main.")

for !rf.killed() {

// Wait for state transition

state := <-rf.controlCh

// Do not block inside this switch statement

switch state {

case Candidate:

debug.Debug(debug.DInfo, rf.me, "Starting an election...")

go startElection(rf)

case Leader:

debug.Debug(debug.DInfo, rf.me, "Starting leader routine.")

go startLeader(rf)

}

}

}

The above function (using a simplified version of the general concurrency pattern) runs in a separate goroutine from the start. As you can see, it waits for new events (states in this case) from the control channel, which is accessible in other parts of the program. We don’t do anything for the Follower state since it doesn’t require any beyond responding to RPCs and checking election timeout.

main function (running as a goroutine) just kick-starts other functionalities as separate goroutines and it doesn’t block at all. This is necessary to keep your Raft instance responsive for new transitions.Autonomy of child goroutines

In the previous subsection, the main function doesn’t get any termination event from rf.controlCh. You might think coordinating every goroutine tightly is more efficient. However, doing such a thing increases the complexity of your implementation substantially. Instead, it’s easier and faster to implement conditions for termination internally inside your child’s goroutines and not worry about them anymore when you are working on your parent’s (top level) goroutines.

For example, look at the instanceWatchDog goroutines, which is responsible for sending heartbeats to Follower instances from the Leader.

func instanceWatchDog(server int, rf *Raft, term int) {

debug.Debug(debug.DInfo, rf.me, "Starting watchdog for %v.", server)

// ... some initialization

for {

rf.mu.Lock()

// Consistency check

if rf.killed() || rf.state != Leader || rf.currentTerm != term {

debug.Debug(debug.DConsist, rf.me, "Watchdog state is inconsistent. isKilled:%v, state:%v, curTerm:%v, watchdogTerm: %v",

rf.killed(), rf.state, rf.currentTerm, term)

rf.mu.Unlock()

return

}

rf.mu.Unlock()

// ... other functionalities implemented using the general pattern

}

}

As you can see, this function constantly performs consistency checks. If these checks fail, they terminate itself. In my opinion, the most important condition is checking for the current term. In my design, every watchdog instance is dedicated to a specific term. As a result, in the next term, the leader doesn’t have to worry about old watchdogs and they can start new ones safely without compromising performance. This is exactly one of the use cases in distributed systems that having a programming language with a garbage collection mechanism makes a lot of difference because we, as programmers, don’t have to worry about garbage from old watchdogs and the code will be much simpler and cleaner.

Simultaneously handling client-like and server-like responsibilities

As I said before, in Raft, especially when you are in Candidate and Leader states, you have to engage in operations that are client-like (meaning that you have to start it and wait for its result) and server-like (meaning that you have to wait for some other entity to initiate a procedure to produce the results). Again, from my experience, a lot of new developers have difficulty handling these scenarios. In these cases you just have to remember a simple sentence: In distributed systems, all you need are watchdogs and heartbeats.

Let’s discuss them more closely. watchdogs are entities that wait for some event, such as a timeout, to perform something. In the case of Raft, the Leader with create a watchdog for every Follower. This watchdog is responsible for sending AppendEntries RPC. The following is a part of this watchdog implementation:

select {

case <-timer.C:

debug.Debug(debug.DTimer, rf.me, "Watchdog for %v timeout.", server)

timer.Reset(timeout)

go appendEntriesWrapper(rf, server)

case flag := <-ch:

switch flag {

case 0:

// Received reply of AppendEntries RPC with zero entries

//Do something like timer.Reset(timeout)

case 1:

// Received reply of AppendEntries RPC with non-zero entries

// Do something like this:

// timer.Reset(timeout)

// go appendEntriesWrapper(rf, server)

case 2:

// Received a new entry from the client

timer.Reset(timeout)

go appendEntriesWrapper(rf, server)

}

}

You might ask why am I not sending the AppendEntries Response to facilitate committing new entries in Followers. This this is because one of the test cases provided by course instructors named TestCount2B limits the number of RPCs allowed for the implementation. Consequently, I am sending this RPC only when receiving a new entry or after a timeout in the batch.

Now, let’s talk about heartbeats. These are simple RPCs to just check whether a specific entity is alive and responsive or not. Usually, they are used in conjunction with timers to make sure something gets done in a specific amount of time. For instance, in our watchdog implementation, one of the select branches is waiting on a timer. When this timer goes off, we reset it and send a heartbeat.

Applying entries to the state machine

Any instance, regardless of its state, has to apply committed entries to its state machine. In this lab, this is done by sending a message (containing the actual command and term of the entry) through applyCh provided by the upper layer service. Before going further, you should keep in mind that reading from and writing to a channel is potentially blocking. Also, committed entries should be applied in order. In this situation, let’s consider the part of the code that has to apply for new entries (it can be any number of entries) because commitIndex has been updated as a result of receiving an AppendEntries RPC. This code can look like this:

if rf.commitIndex > rf.lastApplied {

rf.mu.Lock()

// ... Checking some initial conditions

updateCount := rf.commitIndex - rf.lastApplied

for i := 0; i < updateCount; i++ {

// ... more checking

rf.lastApplied += 1

entry, ok := rf.log.Get(rf.lastApplied)

if ok {

// ... applying the entry using applyCh

}

}

debug.Debug(debug.DCommit, rf.me, "Updated lastApplied: %v --> %v.",

oldLastApplied, rf.lastApplied)

rf.mu.Unlock()

}

Let me mention some points about this piece of code:

- This section of the code certainly is a critical section because other goroutines handling

AppendEntriesresponses might want to updatecommitIndexandlastApplied(noticeLockandUnlockoperations). - As I said before, sending through a channel (in this case

applyChcan potentially be blocked because the user of this channel might not read from it for an unknown amount of time). - There might be more than one entry to be applied and we cannot unlock between iterations of the loop because interleaving of goroutines caused by Go’s runtime scheduler can disrupt the order in which we are applying the entries.

So, what we can do in this scenario? Let us go through some possible designs for solving this challenge.

Option 1

Idea: Store entries that need to be applied in a data structure that preserves their order (like a list) in the critical section. Then apply them one by one after ending the critical section.

Evaluation: Suppose we have two goroutines handling AppendEntries responses (goroutine #1 and #2). goroutine #1 stores entries 1 to 3. Then, it closes the critical section. However, before it can apply these three entries to the state machine, goroutine #2 comes around and stores entries 4 and 5 in a list and applies them (remember that our calculations in the critical section are protected against data races, so no other goroutine can get entries 1, 2, and 3 after #1). Consequently, the ordering condition is not met and the design is wrong.

Option 2

Idea: Again suppose the situation in Option 1, but in this design, each goroutine decides to run a separate goroutine that applies for entries (that goroutine doesn’t require the lock). They start this child goroutine inside the critical section.

Evaluation: Since child goroutines do not require any locking, the scheduler can interleave them somehow so that the order gets disrupted exactly like Option 1.

Option 3

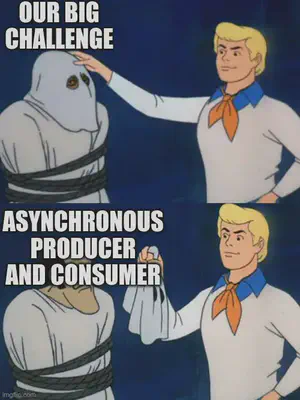

After failing two times, let’s think and find the main challenge in our designs. Because sending on the channel might block, in our previous designs, we had to do this operation out of the critical section that caused out-of-order applied entries.

We need to apply messages somehow in the critical section without blocking!

This might seem a big problem at first glance, but actually, it’s an old and well-thought problem in computer science especially among people who are working on system programming. This challenge is known as asynchronous producer and consumer. In our case, we have to deal with the critical section too! (to keep it from getting too boring!!)

Let me elaborate on our desired situation. First, we need a goroutine waiting on a channel to receive entries to be applied and storing these entries in an internal queue. Second, a goroutine applies for entries in the internal queue.

entries := make([]*LogEntry, 0)

var mu sync.Mutex

ch := make(chan int)

// ## Goroutine 1 ##

/* Goroutine responsible for receiving new entries to apply from

AppendEntries handler and queueing them */

go func() {

for !rf.killed() {

// internalApplyCh is used by the RPC response handler to send to-be-applied

// entries

e := <-rf.internalApplyCh

mu.Lock()

entries = append(entries, e)

mu.Unlock()

select {

case ch <- 0:

default: // Note that select won't block because of this

}

}

}()

// ## Goroutine 2 ##

// Code responsible for reading from the internal queue of entries and applying them

for {

if rf.killed() {

return

}

// Checking the internal queue without busy waiting

mu.Lock()

for len(entries) < 1 {

mu.Unlock()

<-ch

mu.Lock()

}

e := entries[0]

entries = entries[1:]

mu.Unlock()

rf.applyCh <- ApplyMsg{

CommandValid: true,

Command: e.Command,

CommandIndex: e.Index,

}

debug.Debug(debug.DCommit, rf.me, "Applied index:%v.", e.Index)

}

Some interesting points:

- Goroutine 1 does not block at all (The internal lock is only acquired for a short amount of times in both goroutines). Also, don’t confuse this internal lock with the global lock protecting critical sections.

- Goroutine 2 waits for new entries in the internal queue but it does not busy wait. Pro tip: the pattern for checking the length of the queue without busy waiting greatly resembles condition variables, but in this case, I am using the channel for signaling!

- Goroutine number 2 might block when applying for an entry, but this is absolutely fine since our main goal was to prevent Raft from blocking and preserving the order when applying for entries.

Now the critical section in the AppendEntries response handler can send a notification through rf.internalApplyCh without worrying about blocking or compromising the order of applied log entries.

Final notes

- Do not block any interface to upper-level services, such as the state machine, that are using Raft for distributed consensus. This is important because you don’t know how these upper-level services might use this interface.

- Do not forget about careful logging. Otherwise, debugging such complex distributed systems would be almost impossible. More about logging in the Lab’s page and my solutions repository.

If you have any questions or notes regarding the implementation of this post, please don’t hesitate to let me know via email or any other contact point.